Experiment with Moq, an approach to writing mocks

Recently I was looking into a new way to use mocks in my unit tests. My framework of choice to write unit tests is XUnit, whereas I use Moq to create Mocks. The theory behind Moq will still apply if you use a different testing framework, and perhaps some of the things I will demonstrate will be possible in other mocking frameworks.

In many projects, I find that we look at essential things like:

- How should the architecture look?

- Which design patterns should we use?

- Making sure we follow the SOLID principles.

- How should we structure our code base?

At the same time, I find that we do not give our tests the same amount of love.

Wouter Roos, a colleague of mine over at ilionx, gave me this idea, and after experimenting a bit with it, I like it so much that I decided to blog about it. I tried hard to find other articles about it but did not find a post doing something similar. It wanted to make sure that the idea would also transfer to other aspects like how to mock ILogger<T>, that I stumbled upon an excellent article by Adam Storr. Coincidentally Adam linked to a part in a series by Matthew Jones about Fluent Mocks. I have been reading articles written by Matthew for some time now but missed this one. Matthews approach and, for that matter, Adam's proposal on testing ILogger are not quite the same as what I will propose, but I think these ideas will complement each other nicely. Funnily enough, I have had Adam's idea to create extensions methods on Mock<T> before when setting up a mock filesystem for use in unit tests. However, I can extend on that premise with what I learned from Wouter and make it even better.

System Setup

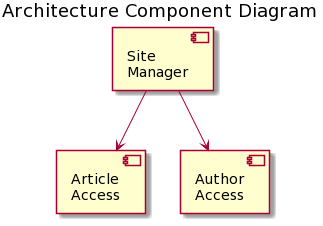

Bear with me for a little while whilst we set up our demo scenario. In our architecture, we have defined three components. We have two resource access components and one manager. The manager is used to orchestrate our business code, and the resource access components interact with a resource, for example, a database.

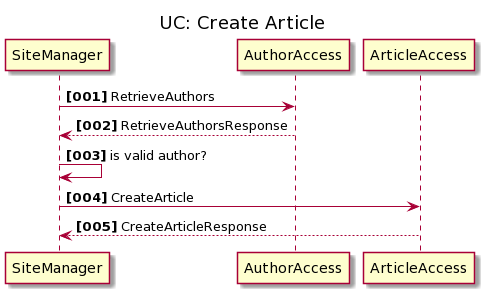

Since I am writing this blog post, what better example than a use case for a blogging platform. Imagine a platform where users can create and share their content. But you can only successfully start posts after you verified your account. In a sequence diagram, it might look something like this.

I am going to use the dotnet CLI to create my project structure.

dotnet new sln

dotnet new classlib --name Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Article.Interface --output src/Components/Access/Article/Interface --framework netstandard2.1

dotnet new classlib --name Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Article.Service --output src/Components/Access/Article/Service --framework netstandard2.1

dotnet new classlib --name Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Author.Interface --output src/Components/Access/Author/Interface --framework netstandard2.1

dotnet new classlib --name Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Author.Service --output src/Components/Access/Author/Service --framework netstandard2.1

dotnet new classlib --name Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Manager.Site.Interface --output src/Components/Manager/Site/Interface --framework netstandard2.1

dotnet new classlib --name Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Manager.Site.Service --output src/Components/Manager/Site/Service --framework netstandard2.1

dotnet new xunit --name Test.Unit --output test/Unit --framework netcoreapp3.1

└── src

│ └── Components

│ │ └── Access

│ │ │ └── Article

│ │ │ │ └── Interface

│ │ │ │ └── Service

│ │ │ └── Author

│ │ │ │ └── Interface

│ │ │ │ └── Service

│ │ └── Manager

│ │ │ └── Site

│ │ │ │ └── Interface

│ │ │ │ └── Service

└── test

│ └── Unit

If everything went fine, you should have the following directory structure on disk. I like to split my components into an interface definition project and an actual implementation project. This split, of course, means that every .Service project needs to reference the corresponding .Interface project via ProjectReference. Because of our architecture, the SiteManager service needs to reference the interface projects of both access services. Finally, our unit test project needs to reference the service projects so we can test them.

You may be wondering why I specified

--frameworkafter each dotnet new command; this is because it would otherwise default toNET5.0, which would be fine for a blog post like this, but since NET5 is not LTS, I mostly abstain from using it in my projects.

I will not include every little DTO as part of this article since those classes will be available as part of the source code in the end. For now, assume we have created our implementation to look like this.

Our Article Access

using System;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Article.Interface;

namespace Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Article.Service

{

public class ArticleAccess : IArticleAccess

{

public Task<CreateArticlesResponse> CreateArticles(CreateArticlesRequest createArticlesRequest)

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

public Task DeleteArticles(DeleteArticlesRequest deleteArticlesRequest)

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

public Task<FilterArticleResponse> FilterArticles(FilterArticleCriteria filterArticleCriteria = null)

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

}

}

Our Author Access

using System;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Author.Interface;

namespace Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Author.Service

{

public class AuthorAccess : IAuthorAccess

{

public Task<FilterAuthorResponse> FilterAuthors(FilterAuthorCriteria filterAuthorCriteria = null)

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

}

}

And finally, our Site Manager, which should match our sequence diagram, looks like this.

using System.Linq;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Article.Interface;

using Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Author.Interface;

using Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Manager.Site.Interface;

namespace Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Manager.Site.Service

{

public class SiteManager : ISiteManager

{

private readonly IArticleAccess _articleAccess;

private readonly IAuthorAccess _authorAccess;

public SiteManager(IArticleAccess articleAccess, IAuthorAccess authorAccess)

{

_articleAccess = articleAccess;

_authorAccess = authorAccess;

}

public async Task CreateArticle(Interface.CreateArticleRequest createArticleRequest)

{

// Hardcoded for now, would probably come from JWT user claim.

var authorId = 666;

var authorsResponse = await _authorAccess.FilterAuthors(new FilterAuthorCriteria {

AuthorIds = new int[] { authorId }

});

var author = authorsResponse.Authors.SingleOrDefault(x => x.Id.Equals(authorId));

if (author == null)

{

return;

}

if (!author.Verfied)

{

return;

}

var article = new Access.Article.Interface.CreateArticleRequest

{

AuthorId = authorId,

Title = createArticleRequest.Title,

Description = createArticleRequest.Content

};

var response = await _articleAccess.CreateArticles(new CreateArticlesRequest {

CreateArticleRequests = new Access.Article.Interface.CreateArticleRequest[] {

article

}

});

}

}

}

Wait just a minute! You forgot to implement the access components and only gave us the manager one. I did not ;-) It is to prove a point. Since we are going to mock our dependencies, we don't use the actual implementation.

Thank you for bearing with me; now that we have all that in place, we can finally get to the heart of the matter and start our adventure with Mock.

The Problem

I have yet to explain the reason behind the article. Let us look at how we might test this code traditionally with the following snippet.

[Fact]

public async Task Test_SiteManager_CreateArticle_Traditionally()

{

// Arange

var authorAccessMock = new Mock<IAuthorAccess>();

authorAccessMock.Setup(x => x.FilterAuthors(It.Is<FilterAuthorCriteria>(p => p.AuthorIds.Contains(666)))).ReturnsAsync(new FilterAuthorResponse {

Authors = new Author[] {

new Author {

Id = 666,

DisplayName = "Max",

Verfied = true

}

}

});

var articleAccessMock = new Mock<IArticleAccess>();

articleAccessMock.Setup(x => x.CreateArticles(It.IsAny<CreateArticlesRequest>())).ReturnsAsync(new CreateArticlesResponse {

Articles = new Article[] {

new Article {

Id = 1,

AuthorId = 666,

Title = "...",

Description = "..."

}

}

});

ISiteManager sut = new SiteManager(articleAccessMock.Object, authorAccessMock.Object);

// Act

var request = new Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Manager.Site.Interface.CreateArticleRequest {

Title = "Pretty Title",

Content = "# AdventuresWithMock ..."

};

await sut.CreateArticle(request);

// Assert

authorAccessMock.Verify(x => x.FilterAuthors(It.IsAny<FilterAuthorCriteria>()), Times.Once);

articleAccessMock.Verify(x => x.CreateArticles(It.IsAny<CreateArticlesRequest>()), Times.Once);

}

That is a lot of code to test a simple scenario. It is in its current form, even four lines longer than the code under test. Even worse, it's primarily boilerplate to set up the test. I often find myself repeating similar code for every test. Which is a violation of the "Don't Repeat Yourself" principle. So I am going to propose an alternative set up to my mock code. All you need to do is create a subclass from Mock<T> for the system you want to stub, and you are good to go.

Mocking Data Access

We start with the AuthorsAccessMock. We will use our constructor to pass a List<Author> and use Moq's Setup method to return the internal state. Yes, that's right, because our mock is now a class we are stateful, this means we can now track state and changes on our mocks without relying on the Verify method.

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Author.Interface;

using Moq;

namespace Test.Unit.Mocks

{

public class AuthorAccessMock : Mock<IAuthorAccess>

{

public List<Author> Authors { get; }

public AuthorAccessMock(List<Author> authors)

{

Authors = authors;

Setup(x => x.FilterAuthors(It.IsAny<FilterAuthorCriteria>()))

.ReturnsAsync((FilterAuthorCriteria criteria) => {

IQueryable<Author> result = Authors.AsQueryable();

if (criteria != null)

{

result = result.Where(x => criteria.AuthorIds.Contains(x.Id));

}

return new FilterAuthorResponse {

Authors = result.ToArray()

};

});

}

}

}

So how does this impact our test? We create a new AuthorAccessMock and pass it to our system under test. Keep in mind this is still a Mock<T>, so to give it, we do authorAccessMock.Object. Our new setup drastically decreases the setup code in my test, and at the same time, it increases the reusability of my mocks

[Fact]

public async Task Test_SiteManager_CreateArticle_RepoMocksDemo1()

{

// Arange

var authorAccessMock = new AuthorAccessMock(new List<Author> {

new Author { Id = 666, DisplayName = "Max", Verfied = false }

});

var articleAccessMock = new ArticleAccessMock();

ISiteManager sut = new SiteManager(articleAccessMock.Object, authorAccessMock.Object);

// Act

var request = new Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Manager.Site.Interface.CreateArticleRequest

{

Title = "Pretty Title",

Content = "# AdventuresWithMock ..."

};

await sut.CreateArticle(request);

// Assert

authorAccessMock.Verify(x => x.FilterAuthors(It.IsAny<FilterAuthorCriteria>()), Times.Once);

articleAccessMock.Verify(x => x.CreateArticles(It.IsAny<CreateArticlesRequest>()), Times.Never);

}

Our AuthorAccess was a bit boring. Let's extend on the stateful premise by building our ArticleAccessMock, which looks a lot like a CRUD repository. There are a couple of things in the following snippet I like to point out.

- I created another representation of our Article class, and this is so that our mock implementation does a soft delete. Since we are stateful, we can then make tests on that premise.

- I also track the requests DTOs to my service using Moq's Callback mechanism. This way, I can make assertions regarding the actual input request.

- I partially moved away from constructor set up to demonstrate this pattern nicely complements Matthew's FluentMocks pattern.

- Lastly, I also added a custom verify method, which takes a func as an argument; this makes it possible to write any validation I can imagine against my internal state.

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Access.Article.Interface;

using Moq;

namespace Test.Unit.Mocks

{

public class ArticleAccessMock : Mock<IArticleAccess>

{

public class ArticleMock

{

public int Id { get;set; }

public int AuthorId { get;set; }

public string Title { get;set; }

public string Content { get;set; }

public bool Removed { get;set; }

}

public List<CreateArticlesRequest> CreateArticlesRequests { get; } = new List<CreateArticlesRequest>();

public List<DeleteArticlesRequest> DeleteArticlesRequests { get; } = new List<DeleteArticlesRequest>();

private List<ArticleMock> _articleState = new List<ArticleMock>();

private int _numberOfArticlesBeforeCreate = 0;

public ArticleAccessMock()

{

Setup(access => access.CreateArticles(It.IsAny<CreateArticlesRequest>()))

.Callback<CreateArticlesRequest>(request => {

CreateArticlesRequests.Add(request);

_numberOfArticlesBeforeCreate = _articleState.Count;

var nextId = _numberOfArticlesBeforeCreate + 1;

foreach(var createArticleRequest in request.CreateArticleRequests)

{

_articleState.Add(new ArticleMock {

Id = nextId,

AuthorId = createArticleRequest.AuthorId,

Content = createArticleRequest.Description,

Title = createArticleRequest.Title,

Removed = false

});

nextId++;

}

})

.ReturnsAsync(() => new CreateArticlesResponse {

Articles = _articleState

.Skip(_numberOfArticlesBeforeCreate)

.Select(x => new Article

{

Id = x.Id,

AuthorId = x.AuthorId,

Description = x.Content,

Title = x.Title

})

.ToArray()

});

Setup(access => access.DeleteArticles(It.IsAny<DeleteArticlesRequest>()))

.Callback<DeleteArticlesRequest>(deleteArticlesRequest => {

DeleteArticlesRequests.Add(deleteArticlesRequest);

foreach(var deleteArticleRequests in deleteArticlesRequest.DeleteArticleRequests)

{

var existing = _articleState.SingleOrDefault(article => deleteArticleRequests.ArticleId == article.Id);

if (existing != null)

{

existing.Removed = true;

}

}

});

}

public ArticleAccessMock SetupFilterArticles(List<Article> articles)

{

_articleState = articles.Select(x => new ArticleMock {

Id = x.Id,

AuthorId = x.AuthorId,

Content = x.Description,

Title = x.Title,

Removed = false

}).ToList();

Setup(x => x.FilterArticles(It.IsAny<FilterArticleCriteria>()))

.ReturnsAsync((FilterArticleCriteria criteria) => {

IQueryable<ArticleMock> result = _articleState.AsQueryable();

if (criteria != null)

{

result = result.Where(x => criteria.ArticleIds.Contains(x.Id));

}

return new FilterArticleResponse {

Articles = result

.Where(x => !x.Removed)

.Select(x => new Article {

Id = x.Id,

AuthorId = x.AuthorId,

Description = x.Content,

Title = x.Title

})

.ToArray()

};

});

return this;

}

public bool VerifyArticles(Func<List<ArticleMock>, bool> predicate)

{

return predicate(_articleState);

}

}

}

I usually would not write a test for my Moq code. The following snippet's purpose is to demonstrate the statefulness of our mocks. On the other hand, our mocks are now lightweight implementations of service, so why not test them!

[Fact]

public async Task Test_ArticleAccessMock_StatefullDemo1()

{

// Arange

var articleAccessMock = new ArticleAccessMock()

.SetupFilterArticles(new List<Article> {});

var sut = articleAccessMock.Object;

// Act

var initialResponse = await sut.FilterArticles();

var createResponse = await sut.CreateArticles(new CreateArticlesRequest {

CreateArticleRequests = new CreateArticleRequest[] {

new CreateArticleRequest {

AuthorId = 666,

Description = "1",

Title = "1"

},

new CreateArticleRequest {

AuthorId = 666,

Description = "2",

Title = "2"

}

}

});

var afterAddResponse = await sut.FilterArticles();

await sut.DeleteArticles(new DeleteArticlesRequest {

DeleteArticleRequests = new DeleteArticleRequest[] {

new DeleteArticleRequest {

ArticleId = createResponse.Articles.First().Id

}

}

});

var afterRemoveResponse = await sut.FilterArticles();

// Assert

initialResponse.Should().NotBeNull();

initialResponse.Articles.Count().Should().Be(0, "No articles initially");

afterAddResponse.Should().NotBeNull();

afterAddResponse.Articles.Count().Should().Be(2, "We created two articles");

afterRemoveResponse.Should().NotBeNull();

afterRemoveResponse.Articles.Count().Should().Be(1, "There is only one article left");

// Verify result with predicate logic instead if Mock.Verify()

articleAccessMock.VerifyArticles(articles => articles.Count(x => x.Removed) == 1).Should().BeTrue();

}

You might ask yourself; Max, if you use a constructor to set up our mock, how would I deviate in my tests if I want to test error scenarios, for example? In that case, we might as well go full circle with the Fluent Mock approach. You could do it like the following snippet. You then choose to use the 'default' stateful mock or call the Setup methods you want to use.

public ArticleAccessMock MakeStateful(List<Article> articles)

{

return this

.SetupFilterArticles(articles)

.SetupDeleteArticles()

.SetupCreateArticles();

}

public ArticleAccessMock SetupDeleteArticles() { /* ... */ }

public ArticleAccessMock SetupCreateArticles() { /* ... */ }

Mocking ILogger

I did say that Adam's article also inspired me. So let us see how ILogger can implement stateful mocks. First, a quick reminder of what we are going to Mock. The ILogger interface looks like this.

/// <summary>

/// Writes a log entry.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="logLevel">Entry will be written on this level.</param>

/// <param name="eventId">Id of the event.</param>

/// <param name="state">The entry to be written. Can be also an object.</param>

/// <param name="exception">The exception related to this entry.</param>

/// <param name="formatter">Function to create a <see cref="string"/> message of the <paramref name="state"/> and <paramref name="exception"/>.</param>

/// <typeparam name="TState">The type of the object to be written.</typeparam>

void Log<TState>(LogLevel logLevel, EventId eventId, TState state, Exception? exception, Func<TState, Exception?, string> formatter);

I can not express how happy I am that I don't need to call the Logger like that. Luckily Microsoft offers a different extension method for every occasion. Unfortunately, Moq cannot test extension methods. Luckily for me, Adam figured out how to test it.

Create a LoggerMock<T> class that implements Mock<ILogger<T>> we are not going to add something custom to it just yet.

using Microsoft.Extensions.Logging;

using Moq;

namespace Test.Unit.Mocks

{

public class LoggerMock<T> : Mock<ILogger<T>>

{

}

}

At the same time, we will use the final result from Adam's post as a helper method to test our logging.

public static Mock<ILogger<T>> VerifyLogging<T>(this Mock<ILogger<T>> logger, string expectedMessage, LogLevel expectedLogLevel = LogLevel.Debug, Times? times = null)

{

times ??= Times.Once();

Func<object, Type, bool> state = (v, t) => v.ToString().CompareTo(expectedMessage) == 0;

logger.Verify(

x => x.Log(

It.Is<LogLevel>(l => l == expectedLogLevel),

It.IsAny<EventId>(),

It.Is<It.IsAnyType>((v, t) => state(v, t)),

It.IsAny<Exception>(),

It.Is<Func<It.IsAnyType, Exception, string>>((v, t) => true)), (Times)times);

return logger;

}

With that in place, let's update the manager to log.

public class SiteManager : ISiteManager

{

// ...

private readonly ILogger _logger;

public SiteManager(IArticleAccess articleAccess, IAuthorAccess authorAccess, ILogger<SiteManager> logger)

{

// ...

_logger = logger;

}

public async Task CreateArticle(Interface.CreateArticleRequest createArticleRequest)

{

// Hardcoded for now, would probably come from JWT user claim.

var authorId = 666;

/// ...

if (author == null)

{

_logger.LogWarning($"No author found for {authorId}");

return;

}

// ...

}

}

To put it to the test:

[Fact]

public async Task Test_SiteManager_CreateArticle_TestLogging()

{

// Arange

var loggerMock = new LoggerMock<SiteManager>();

var authorAccessMock = new AuthorAccessMock(new List<Author> {});

var articleAccessMock = new ArticleAccessMock();

ISiteManager sut = new SiteManager(articleAccessMock.Object, authorAccessMock.Object, loggerMock.Object);

// Act

var request = new Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Manager.Site.Interface.CreateArticleRequest

{

Title = "Pretty Title",

Content = "# AdventuresWithMock ..."

};

await sut.CreateArticle(request);

// Assert

authorAccessMock.Verify(x => x.FilterAuthors(It.IsAny<FilterAuthorCriteria>()), Times.Once);

articleAccessMock.Verify(x => x.CreateArticles(It.IsAny<CreateArticlesRequest>()), Times.Never);

loggerMock.VerifyLogging("No author found for 666", Microsoft.Extensions.Logging.LogLevel.Warning);

}

Wait, did that just work on the first try? Did Adam's extension method not work on Mock<ILogger<T>>? Remember subclassing is an is a relation ship which means that our MockLogger qualifies for this extension method.

What would happen if have a lot of traffic and log thousands upon thousands of requests. In that case, we can move to an alternative for methods such as LogInformation. For these scenarios, you can use LoggerMessage for high-performance logging.

using System;

using Microsoft.Extensions.Logging;

namespace Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Manager.Site.Service

{

public static class LoggerExtensions

{

private static readonly Action<ILogger, int, Exception> _authorNotVerfied =

LoggerMessage.Define<int>(

LogLevel.Information,

EventIds.AuthorNotVerfied,

"Author with Id {AuthorId} is not verfied!"

);

public static void LogAuthorNotVerfied(this ILogger logger, int authorId)

{

_authorNotVerfied(logger, authorId, null);

}

private static class EventIds

{

public static readonly EventId AuthorNotVerfied = new(100, nameof(AuthorNotVerfied));

}

}

}

[Fact]

public async Task Test_SiteManager_CreateArticle_TestLoggingExtensionMethod()

{

// Arange

var loggerMock = new LoggerMock<SiteManager>();

var authorAccessMock = new AuthorAccessMock(new List<Author> {

new Author { Id = 666, DisplayName = "Max", Verfied = false }

});

var articleAccessMock = new ArticleAccessMock();

ISiteManager sut = new SiteManager(articleAccessMock.Object, authorAccessMock.Object, loggerMock.Object);

// Act

var request = new Kaylumah.AdventuresWithMock.Manager.Site.Interface.CreateArticleRequest

{

Title = "Pretty Title",

Content = "# AdventuresWithMock ..."

};

await sut.CreateArticle(request);

// Assert

authorAccessMock.Verify(x => x.FilterAuthors(It.IsAny<FilterAuthorCriteria>()), Times.Once);

articleAccessMock.Verify(x => x.CreateArticles(It.IsAny<CreateArticlesRequest>()), Times.Never);

loggerMock.VerifyLogging("Author with Id 666 is not verfied!", Microsoft.Extensions.Logging.LogLevel.Information);

loggerMock.VerifyEventIdWasCalled(new Microsoft.Extensions.Logging.EventId(100, "AuthorNotVerfied"));

}

You are probably as surprised as I was that it did not work. As it turns out, LoggerMessage actual checks against LogLevel enabled. So add the following to our LoggerMock.

public LoggerMock<T> SetupLogLevel(LogLevel logLevel, bool enabled = true)

{

Setup(x => x.IsEnabled(It.Is<LogLevel>(p => p.Equals(logLevel))))

.Returns(enabled);

return this;

}

There is one last improvement I wish to make to our LoggerMock. Like our stateful repository mocks, I feel it would be beneficial to capture everything that goes into our mock—in my opinion, using Predicates and Linq gives me more control over my assertions than using mocks internals.

Our final implementation looks like this:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using Microsoft.Extensions.Logging;

using Moq;

namespace Test.Unit.Mocks

{

public class LoggerMock<T> : Mock<ILogger<T>>

{

public class LogMessageMock

{

public LogLevel LogLevel { get;set; }

public EventId Event { get;set; }

public string Message { get;set; }

}

public List<LogMessageMock> Messsages { get; } = new List<LogMessageMock>();

public LoggerMock()

{

Setup(x => x.Log(

It.IsAny<LogLevel>(),

It.IsAny<EventId>(),

It.Is<It.IsAnyType>((v, t) => true),

It.IsAny<Exception>(),

It.Is<Func<It.IsAnyType, Exception, string>>((v, t) => true)

)

)

.Callback(new InvocationAction(invocation =>

{

// https://stackoverflow.com/questions/52707702/how-do-you-mock-ilogger-loginformation

// https://github.com/moq/moq4/issues/918

var logLevel = (LogLevel)invocation.Arguments[0];

var eventId = (EventId)invocation.Arguments[1];

var state = invocation.Arguments[2];

var exception = (Exception?)invocation.Arguments[3];

var formatter = invocation.Arguments[4];

var invokeMethod = formatter

.GetType()

.GetMethod("Invoke");

var logMessage = (string?)invokeMethod?.Invoke(formatter, new[] { state, exception });

Messsages.Add(new LogMessageMock {

Event = eventId,

LogLevel = logLevel,

Message = logMessage

});

}));

}

public LoggerMock<T> SetupLogLevel(LogLevel logLevel, bool enabled = true)

{

Setup(x => x.IsEnabled(It.Is<LogLevel>(p => p.Equals(logLevel))))

.Returns(enabled);

return this;

}

}

}

Mocking HttpClient

Even though our article is getting to be on the length side, I found it helpful to include at least one more example. I could rewrite the filesystem sample I mentioned to match this pattern, but I decided to do that later. I thought it would be more useful to look into mocking an HttpClient. One option would be to hide HttpClient behind an interface, but since our ArticleAccess is already the lowest point in our architecture, I see no need to hide that we use a HttpClient.

Since this is purely a demonstration, I am not going to set up an HTTP Server. Luckily we can use https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts for our needs. Suppose our CreateArticles method looked like this.

public async Task<CreateArticlesResponse> CreateArticles(CreateArticlesRequest createArticlesRequest)

{

// NOTE: not going to call them in a loop, just for demo purposes.

var json = JsonSerializer.Serialize(createArticlesRequest.CreateArticleRequests.First());

var response = await _httpClient.PostAsync("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts", new StringContent(json));

if (!response.IsSuccessStatusCode)

{

throw new Exception("Something went horribly wrong!");

}

var responseText = await response.Content.ReadAsStringAsync();

// Map it to response

return new CreateArticlesResponse {};

}

Unfortunately, you cannot achieve this by mocking HttpClient. You need to Mock HttpMessageHandler. Depending on your needs, it might look something like the following snippet. (Based on this stackoverflow answer)

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Net;

using System.Net.Http;

using System.Threading;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Moq;

using Moq.Language;

using Moq.Protected;

namespace Test.Unit.Mocks

{

public class HttpClientMock : Mock<HttpMessageHandler>

{

private readonly List<Tuple<HttpStatusCode, HttpContent>> _responses;

public HttpClientMock(List<Tuple<HttpStatusCode, HttpContent>> responses) : base(MockBehavior.Strict)

{

_responses = responses;

SetupResponses();

}

private void SetupResponses()

{

var handlerPart = this.Protected().SetupSequence<Task<HttpResponseMessage>>(

"SendAsync",

ItExpr.IsAny<HttpRequestMessage>(),

ItExpr.IsAny<CancellationToken>()

);

foreach (var item in _responses)

{

handlerPart = AdddReturnPart(handlerPart, item.Item1, item.Item2);

}

}

private ISetupSequentialResult<Task<HttpResponseMessage>> AdddReturnPart(ISetupSequentialResult<Task<HttpResponseMessage>> handlerPart,

HttpStatusCode statusCode, HttpContent content)

{

return handlerPart.ReturnsAsync(new HttpResponseMessage()

{

StatusCode = statusCode,

Content = content

});

}

public static implicit operator HttpClient (HttpClientMock mock)

{

// Since neither HttpClient or HttpClientMock is an interface we can use implicit operator to convert.

// Safes us a call to mock.Object in the test code.

return new HttpClient(mock.Object) {};

}

}

}

The corresponding test would look like

[Fact]

public async Task Test_ArticleAccess_Returns200OK()

{

var createArticleResponse = new StringContent("{ 'id':'anId' }", Encoding.UTF8, "application/json");

var httpClient = new HttpClientMock(new List<Tuple<HttpStatusCode, HttpContent>> {

new Tuple<HttpStatusCode, HttpContent>(HttpStatusCode.OK, createArticleResponse),

});

var articleAccess = new ArticleAccess(httpClient);

await articleAccess.CreateArticles(new CreateArticlesRequest{

CreateArticleRequests = new CreateArticleRequest[] {

new CreateArticleRequest {

AuthorId = 666,

Description = "...",

Title = "Demo"

}

}

});

}

Summary

That concludes my experiment for the day. I have shown three instances where you can apply your custom subclasses of Mock<T>. The way I see it, it offers three distinct advantages:

- Test code and mock code is separated.

- Mock code is reusable across tests.

- Stateful mocking allows for more readable verification in tests.

Of course, creating a mock library will take some time. You could argue if it's worth the time to make a duplicate, albeit a simplified version of your data access. My personal opinion is that it makes debugging and reasoning about my tests easier than taking a deep dive in Invocations and Verify mock provides. As I have hopefully demonstrated is that one does not exclude the other. I think it can complement one and other.

I am glad about the early results of my experiment, hence me writing this blog post. Over time you can evolve these mocks to be even better. For example, change tracking of entities could potentially be used cross mock. The HttpClientMock could use some more love. Imagine hiding every detail like StatusCode, HttpResponseMessage from the tester. I could have saved it for another blog, but I shared this abstraction to start a dialogue with my team about testing and test set up.

As always, if you have any questions, feel free to reach out. I am curious to hear what you all think about this approach. Do you have suggestions or alternatives? I would love to hear about them.

The corresponding source code for this article is on GitHub.

See you next time, stay healthy and happy coding to all 🧸!